Pratt R Art Dance and Music Therapy Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2004

Creative Arts Interventions for Stress Direction and Prevention—A Systematic Review

one

Inquiry Institute for Creative Arts Therapies (RIArT), Alanus Academy of Arts and Social Sciences, Alfter/Bonn, Villestr. 3, 53347 Alfter, Germany

2

Section for Therapy Sciences, SRH University Heidelberg, Maria-Probst-Str. 3, 69123 Heidelberg, Germany

iii

Robert-Bosch-Klinik, Auerbachstr. 110, 70376 Stuttgart, Frg

4

Schoen-Klinik, Hofgarten 10, 34454 Bad Arolsen, Deutschland

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: 7 December 2017 / Revised: 11 Feb 2018 / Accepted: thirteen Feb 2018 / Published: 22 February 2018

Abstract

Stress is one of the world's largest wellness problems, leading to exhaustion, exhaustion, anxiety, a weak immune organisation, or even organ impairment. In Federal republic of germany, stress-induced work absenteeism costs most 20 billion Euros per year. Therefore, information technology is non surprising that the Central Federal Clan of the public Health Insurance Funds in Germany ascribes item importance to stress prevention and stress management equally well every bit health enhancing measures. Building on current integrative and embodied stress theories, Artistic Arts Therapies (CATs) or arts interventions are an innovative fashion to forestall stress and improve stress direction. CATs encompass fine art, music, dance/movement, and drama therapy equally their four major modalities. In guild to obtain an overview of CATs and arts interventions' efficacy in the context of stress reduction and direction, nosotros conducted a systematic review with a search in the following data bases: Academic Search Complete, ERIC, Medline, Psyndex, PsycINFO and SocINDEX. Studies were included employing the PICOS principle and rated according to their evidence level. We included 37 studies, 73% of which were randomized controlled trials. 81.1% of the included studies reported a significant reduction of stress in the participants due to interventions of i of the 4 arts modalities.

i. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), stress is currently the world'south near pronounced wellness gamble [1]. Consequences of stress are constant agitation, exhaustion, burnout, helplessness, fear, and eventually a weak immune system or even organ damage [2]. The inability to cope with stress is a take a chance factor for various epidemiologically meaning illnesses: cardiovascular, muscular or skeletal diseases, depression or feet disorders [3]. Russ et al. [4] showed that stress and other psychological health bug accept an effect on the bloodshed take a chance of otherwise healthy individuals. In Germany, for the concluding xv years, health insurance companies accept registered a drastic increase in stress-induced absence at work [5]. Interviewing 1200 German participants from various religious, age, and milieu backgrounds, the health insurance fund Techniker Krankenkasse (TK) [five] found that 6 out of 10 people written report to experience stress privately or at piece of work, with 23% out of those feeling extremely stressed. Stress-induced absence costs German companies about 20 billion Euros annually [5]. Furthermore, non only adults are affected: a comparative study of the WHO institute children and adolescents to be frequently tired and exhausted, to have problems falling asleep, and to present every bit increasingly irritated due to stressful school and life weather [6].

1.1. Stress equally a Grooming to Act

Stress is the most widespread disease of the modern age. Scientists take analyzed stress from a biological [7], psychological [8,9] and sociological [10] point of view and have created a number of explanatory theories and models. The most well-known is the transactional model of stress and coping of Richard Lazarus and his research group (eastward.one thousand., [11,12]). Lazarus and his colleagues conceptualized stress every bit a outcome of the individual'due south appraisal of his or her surround. Information technology emerges, when the individual evaluates a situation or an incident as challenging or threatening (main appraisal) and his or her own coping abilities as insufficient in the lite of the situation's requirements (secondary appraisement) [thirteen]. Stress management, therefore, is an act of cognitive appraisal, which results in a certain coping behavior [12].

Most recent stress theories integrate biomedical, psychosomatic, cognitive-behavioral, and sociological approaches [2]. Building on appraisal theories [12,thirteen], the recent embodiment theory past Peter Payne and Mardi Crane-Godreau [14], assumes that stress emerges when the organism's preparation to act and cope—the so called Preparatory Set up—does not resolve the aversive situation. This could occur, for example, because the behavior is disorganized or inappropriate, or simply because the situation exceeds the coping abilities of the organism (compare the Preparatory Set Theory bv Peter Payne: [14]). A Preparatory Set describes the rapid, largely sub-cortical, organismic preparation to answer to the surround. This preparation involves an system of physical posture and muscle tone, visceral state, affective or motivational state, arousal and orientation of attention, and (subcortical) cerebral expectations [14]. If the aversive situation is not resolved, the circuitous activation of the organism is maintained and the organism stays in constant excitation and eventually is burned-out [fourteen]. Because a Preparatory Set involves the entire organism, leverage points to tackle stress and foster resources can exist manifold and are not restricted to cerebral-behavioral aspects.

1.2. Artistic Arts Therapies and Arts Interventions for Stress Management and Prevention

Due to the increasing mobility, flexibility, and performance demands in today's club, it is causeless that individuals' stress exposures volition increase further in the future [iii]. Therefore, innovative and embodied interventions for stress prevention and health promotion are needed more than ever.

This is where Artistic Arts Therapies (CATs) and arts interventions come in every bit they have into account what Lazarus and colleagues have missed. By conceptualizing trunk, mind, activeness, and perception as a unity, CATs, such as Music, Trip the light fantastic/Movement, Fine art, and Drama Therapy, besides as simple arts interventions, use artistic media to approach the customer on a creative and nonverbal level [15]. In addition to cognitive ways of coping, CATs target (en-)active creation, interoception (trunk experience), and expression in social club to access emotions and modify behavior (embodied appraisement) [16]. Utilizing a solutogenic approach of wellness and illness [17], CATs provide action opportunities geared toward wellness maintenance and focus on health promoting aspects. The recently developed model of embodied aesthetics by Koch [15,xviii,xix] underlines the embodied enactive nature of CATS. Different from conventional therapies, all CATs encourage and enable their clients to actively create or generate. Attending and concentration, for example, are influenced past the perception, exploration, and creation of artistic content likewise every bit by the explicit employ of the body (body perception and expression). The corresponding art media (art, music, dance, theater) thereby provide dissimilar methods to actuate resource and coping abilities and increase action flexibility, cocky-efficacy, and empowerment [18,20,21]. See Box 1 for a short overview on the four principal CATs and a few exemplary fields of application.

Box 1. Overview of the 4 main modalities of CATs.

Creative Arts Therapies (CATs) are generally defined as "the artistic use of the creative media (art, music, drama and dance/movement) as vehicles for non-verbal and/or symbolic advice, within a holding environment, encouraged by a well-defined client-therapist relationship, in order to reach personal and/or social therapeutic goals appropriate for the individual" ([22], p. 46). CATs can and should exist differentiated from arts interventions or artistic activities practical within the context of psychotherapy, counseling, rehabilitation, or medicine [22,23,24]. While arts interventions use the arts to offer primarily artistic experiences with a therapeutic potential, CATs intentionally utilise the arts to offering therapeutic alter. Creative Arts Therapists are registered with an arts therapies professional person association and do within a specific and regulated lawmaking of ethics [22]. CATs and arts interventions encourage clients to express themselves creatively, which is why they are also called expressive therapies or expressive interventions [23,25]. For a further clarification of the terms run across Karkou and Sanderson's discussion and illustration of differences and overalppings of CATs and arts interventions ([22], p. 45).

Music Therapy (MT) is the targeted awarding of music (music perception, production, and reproduction) within a therapeutic relationship in order to regain, maintain, and promote physical and psychological wellness [26]. With the help of dissimilar instruments or one'southward own voice, emotions and fantasies are expressed and experiences of contact created [26,27]. Music, in this context, furthers the ability to experience oneself and others, symbolize and chronicle. Clinically MT is, for example, used with psychiatric patients, neurological patients, or with children with autism [28]. In Fine art Therapy (AT), clients work with different materials (e.thou., h2o colors, crayons, clay). Through the procedure of creation as well as through relating to one's own art work, possibilities of expression are created. Previous experiences can be symbolized and expressed in a rubber way. Through the fostering of symbolization and (nonverbal) communication, new perspectives and insights can be gained [20,29]. Specifically, the revival and/or fostering of creative resources increase self-efficacy and coping abilities in stressful situations [29]. Clinically, AT is used with patients who have had traumatic experiences or oncological patients among others [thirty]. Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT) is defined every bit the therapeutic use of motility to further the emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual and social integration of the private [31]. Physically, DMT stimulates the vestibular and cardiovascular system [32]. Psychologically, embodied impression and expression improve interoception, trunk schema, and body image [32]. Exploring one's own move abilities and limitations helps to increase emotion regulation, impulse control, and relation to reality (for example for people with schizophrenia, see [33]). Experiencing the ain body in aesthetic movement and flow tin can increase cocky-efficacy. This is of particular importance for patients with Parkinson's disease [34].

Drama Therapy (DT) also uses the trunk as a medium. Voice, language, facial expressions and gestures create an "every bit if"-reality that enables the expression and reflection of old and contempo emotions, exam-acting, distancing, balancing of different roles, and the expansion of activity opportunities [35,36]. Traditionally AT, MT, DT, and DMT are mostly employed in psychiatric and psychosomatic settings. In some countries, such equally the UK and State of israel, CATs are as well widely employed in the schoolhouse arrangement.

ane.3. Researching CATs and Arts Interventions in the Context of Stress Prevention and Stress Management

From an empirical point of view, research on CATs and health-restoring arts interventions is metaphorically speaking in its infancy or adolescence. Cartoon from experiential knowledge of individual practitioners a m literature base of operations of case studies and clinical recommendations has adult, with an only recently growing number of evidence-based studies that provide generalizable, and transferable information [37,38]. CATs are used world-wide in a variety of contexts with many different populations. In addition to creative arts therapists, at that place are artists offering creative interventions to the patients in health institutions. They most often work without a therapeutic professional person groundwork, just likewise use the potential of the arts in lodge to foster health. In addition, psychologists, physicians, and other wellness care professions are increasingly discovering the contribution of the arts in their settings and conduct studies to investigate the workings of the "arts in health". To exercise justice to the heterogeneity of creative arts intervention studies in wellness care, this review includes studies on all CATs every bit well equally arts (art, music, dance and drama) interventions. Mere arts interventions include interventions conducted by, for example, an creative person (no licensed creative arts therapist) as well as single session interventions that non necessarily have a therapeutic intention. Both, CATs and arts intervention studies are referred to collectively equally artistic arts interventions. To understand creative arts interventions, and to strengthen their development for example past identifying indications and contraindications, it is indicated to inspect them in diverse practical contexts. The systematic review at hand provides an overview of show-based studies on stress management and stress prevention through creative arts interventions. Its goal is to promote a dialogue with various wellness practitioners and institutions on the potential and limitations of creative arts interventions in the context of stress prevention. To the knowledge of the authors this review is the outset on the topic.

2. Methods

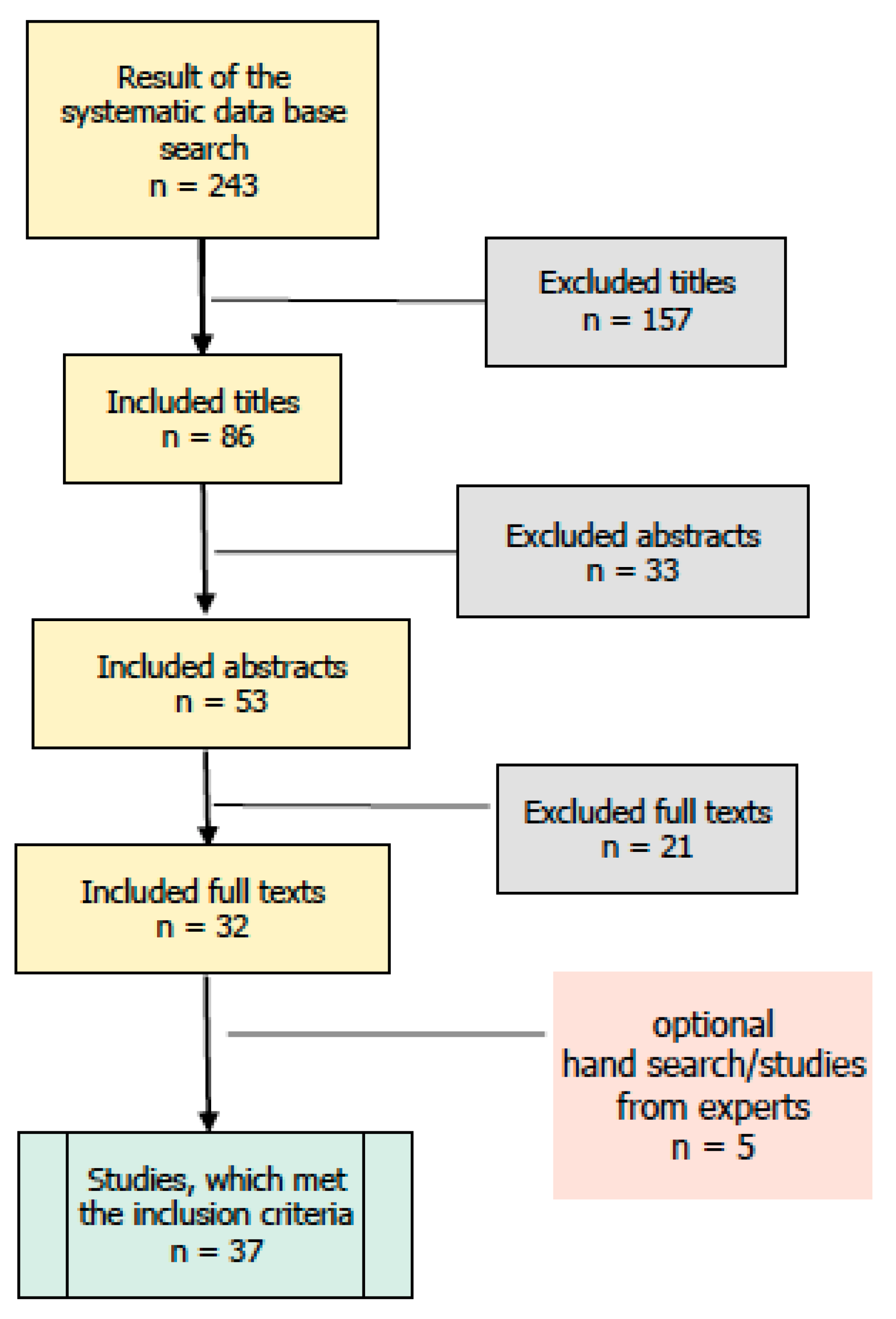

In a systematic data base search, we collected empirical studies from 1980–2016, which investigated CATs or arts interventions in the context of stress prevention. The cutoff engagement for the search was the third of August 2016. In addition, we contacted experts in the field and asked them to hand in studies until the finish of 2016. The following data bases were searched: Bookish Search Complete, ERIC, Medline, Psyndex, PsycINFO, and SocINDEX. Search terms were: art therapy OR art psychotherapy OR creative arts therapies OR drama therapy OR dance therapy OR music therapy AND stress; fine art AND music AND motility therapy; arts AND health OR mental health treatment OR prevention; arts AND professional education OR training. See Figure one for an overview of the search and written report selection process. But studies published in peer-reviewed journals were included.

Process of the Systematic Study Search

The systematic data base of operations search yielded 243 studies. Studies were scanned following the PICOS principle (patient, intervention, control, outcome, study design) [39]. In a first step, the benchmark "patient" was analyzed. To stay in the context of prevention and avoid an overlap with creative arts interventions for acute disorders, for example, in the surface area of mental health, just studies targeting healthy individuals or people at adventure were included. Studies were excluded, if they did not analyze arts interventions in a preventive context. We included both adults and minors, because both groups have been found to be afflicted by stress. After the first round of exclusions on the base of these criteria, 86 studies remained. In a 2d step, the studies were scanned according to the criterion "intervention". Aside from studies that specifically applied CATs, we too included studies, which provided arts interventions (art, dance, music or drama with a group of participants, see reasoning for this decision in a higher place).

In Table 1 CATs are demarcated from mere arts interventions past color coding: clinical studies of CATs are colored greenish, single session studies of CATs and studies on arts interventions are colored black. Single-session interventions conducted by CATs or other professions were rated as mere arts interventions, because those studies exercise not fulfill the criterion of containing a therapeutic procedure with a therapeutic human relationship. Interventions neither had to exist standardized, nor had to have the same duration. This heterogeneity reflects the variability of artistic arts interventions in do. Fifty-three studies remained. We included studies of evidence levels Ia—III. Evidence levels were defined according to the Agency for Healthcare Enquiry and Quality (AHRQ) [40], rated by the first writer and confirmed past the fourth writer. Case studies were excluded. Concerning the criteria "control", "outcome", and "study-design", studies should at least operate with a quasi-experimental design, preferably have a control group, and should clearly state their outcome variables. Qualitative, quantitative, as well as mixed method studies were included, as long as their method was conspicuously stated (in the qualitative realm, e.g., content analysis after Mayring [41]). After checking the remaining studies for those criteria, 32 studies remained. Five studies were handed in by experts after the cutting-off date and thoroughly checked for the criteria named to a higher place. In total, we analyzed and compared 37 studies.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes content, sample, and intervention characteristics, pattern, research methods, and results of the studies identified [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,lxx,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. In total, 37 studies met our inclusion criteria, 11 studies (29.7%) investigated the upshot of AT or art interventions on stress, 20 studies (54.1%) focused on MT or musical interventions, and half dozen studies (16.2%) assessed the effects of DMT or dance interventions. There were no studies on DT or drama interventions that met the inclusion criteria. In total, 2136 subjects were included: 465 took office in AT or fine art interventions for stress management, 1241 in MT or musical interventions, and 430 in DMT or dance interventions. Nigh participants were women (see Tabular array 1). Some studies did not display demographic data of their samples, and were omitted in the respective calculations. The mean age of participants was 1000 = 32.18 years (AT: M = 27.54 years, MT: M = 35.42 years, DMT: M = 33.59 years). Elapsing times of interventions varied from single sessions on i day to weekly sessions for 10 weeks. Due to the great heterogeneity of interventions and the lack of reported effect sizes in many of the single studies, we did not calculate an overall effect size for the arts modalities. Due to infinite limitations only the near cardinal qualitative and quantitative results of the included studies are displayed.

Table 2 gives an analytical overview of the numbers of respective studies by arts modality. As presumed earlier, about of the studies were conducted and published after 2000. Simply five studies (13.5%) were published between 1980 and 1999, iv of them on musical interventions, one on MT. No meta-analysis (show level Ia) was plant on CATs or arts interventions for stress direction and stress prevention. In total, we plant 27 randomized controlled trials (RCTs, evidence level Ib), accounting for 73% of the included studies. Ten of the RCTs analyzed CATs, the remaining seventeen examined the effects of arts interventions. Five studies (13.5%) were rated testify level IIa (2 on CATs, iii on arts interventions), ii studies (5.4%) were rated prove level IIb (all on arts interventions), and three studies (8.one%) bear witness level III (all on arts interventions). Nigh of the studies (16; 59.iii%) on the highest prove level came from the area of Music: 9 studies analyzed MT, seven examined music interventions. With eight studies, AT provided 29.half-dozen% of the studies on testify level Ib (none on AT, all on art interventions), and DMT contributed eleven.1% (3 studies; i on DMT, two on dance interventions). Within the arts modalities 72.7% (AT and fine art interventions), 80% (MT and music interventions) and l% (DMT and dance interventions) of the included studies were RCTs. Well-nigh therapy intervention studies (with several intervention sessions) were institute in MT (xi out of 20) and one in DMT (1 out of half-dozen). In AT, only studies on effects of artistic activities or single-session interventions were found.

Active art interventions, such as drawing or working with clay significantly reduced stress and anxiety in eight out of 11 studies [42,44,45,46,49,l,51,52]. None of the studies analyzed the effects of continuous interventions specifically defined as AT, Three studies [46,51,52] reported significant positive mood changes. Two studies [47,48] did non discover a significant stress reduction or mood changes. Two studies [43,51] stated that stress reduction depended on the content of the art work: positive content induced stress reduction, negative content did not. Stress was assessed with various different instruments, such as the Stress Describing word Checklist, the State-Trait Feet Inventory, The Global Measure of Perceived Stress, or the Perceived Stress Questionnaire. 2 of the studies [45,fifty] used concrete measures (cortisol level [45]; pulse and claret pressure [l]) to operationalize stress. MT or musical interventions reduced stress and anxiety in 16 of xx studies (10 on MT, six on music interventions) [53,54,56,57,58,59,threescore,61,62,63,65,66,67,68,70,72]. Four studies (one of MT, 3 on music interventions) [53,61,68,70] reported reductions in cortisol level, as a concrete measurement of stress, and ii studies (both on MT) [53,58] found a subtract of sleeping problems through musical interventions. Four studies (one on MT, three on music interventions) [55,59,64] did not notice a significant reduction of their stress outcomes.

All studies analyzing DMT or dance interventions found a significant reduction of stress signs or stress coping abilities in their subjects. Only one of the studies analyzed the furnishings of DT. In all merely 2 studies [75,76] stress was measured by different self-evaluation tests. In the ii other studies, stress was tested with saliva samples for cortisol levels. Iv studies [73,74,75,76] furthermore reported a decrease in anxiety levels and negative affect.

In full, stress was significantly reduced in xxx out of 37 included studies (81.1%). 11 out of twelve (91.7%) included studies on CATs institute a meaning stress reduction. Nineteen out of 25 (76%) included studies on mere arts interventions found a significant reduction in their stress measurement.

4. Give-and-take

Recently, besides beingness an important office in clinical health care practice, creative arts interventions have become an important area of integrative medicine enquiry. Despite the novelty of CATs, a notable evidence-base on the efficacy of creative arts interventions in various contexts and with many different populations is emerging.

In the context of stress prevention, the quality of efficacy studies analyzing creative arts interventions is high. Iii quarters of the included studies could exist allocated to evidence level I and over 80% found a pregnant comeback in ane of their stress-related outcomes. Looking at CATs, conducted by licensed therapists, the per centum rises to more than than xc%. Like to other health care contexts, MT and music interventions contribute the highest quality studies. This can be attributed to the comparably early on establishment of MT, its specific focus on group therapy as well as its comparably low psychoanalytic and high empirical orientation (see [25]). CATs and creative arts interventions seem to have a positive impact on perceived stress and stress management. They reduce anxiety levels and meliorate subjects' mood. This may be due to sure therapeutic mechanisms that researchers presume to be relevant for all artistic arts therapies. Hedonism/play, artful feel/authenticity, nonverbal advice/symbolizing, test-interim in an enactive transitional space, and creation/generativity are named every bit therapeutic mechanisms, which are active across all CATs ([xviii,xix]; compare [25]). Information technology remains mostly unclear how these therapeutic mechanisms collaborate or whether they are active in all clients and contexts. Their empirical validation is a task for future research.

Artistic arts interventions' impact on perceived stress and stress direction could not be evaluated past means of an overall effect size for each arts modality. Very few of the studies conspicuously reported all necessary statistics needed for the adding of effect sizes. Some did not even report the full demographic data. Furthermore, varying interventions in content and elapsing impede a last statement on creative arts interventions' efficacy in the context of stress prevention. This high heterogeneity might be the biggest trouble of the young academic field. Being a benefit of the creative approach in practice, the variety of procedures, methods, and interventions makes it hard to assess and judge creative arts interventions' efficacy with conventional bear witness-based inquiry. The high heterogeneity of interventions and measures makes the application of meta-analyses difficult. This is true not only across creative arts interventions but also within each single arts modality (art, music, dance, drama). Information technology might thus be worth looking at specific and common features of the individual CATs, delineating them from mere arts interventions and starting to chronicle them to features of populations and contexts. This may be a expert fashion to find out, what is specific about each arts modality, and which contexts they work best in (indications and contraindications; see for example [25,78,79,80]). Demarcating cadre characteristics and mechanisms of CATs or arts interventions individually besides helps to choose an adequate control group for intervention studies. Finally, finding commonalities across artistic arts interventions could help clarify the benefit they bring to the health system and its agents. Patients already acknowledge these benefits, and the evidence-base on creative arts interventions is in the procedure of being congenital.

Acknowledgments

The review was conducted at the Inquiry Institute for Artistic Arts Therapies (RIArT) at Alanus Academy for Arts and Social Sciences in Alfter/Bonn, Germany. Nosotros would similar to thank the Software AG Foundation (SAGST) for funding.

Author Contributions

S.Chiliad. and K.Grand. initiated the study; R.O. did the systematic data base search; L.M. supervised the systematic data base search; L.M. & R.O. divers inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of involvement.

References

- Korczak, D.; Kister, C.; Huber, B. Differentialdiagnostik des Burnout-Syndroms; Schriftenreihe Health Engineering Assessment (HTA) in der Bundesrepublik Frg: Köln, Germany, 2010; Available online: https://portal.dimdi.de/de/hta/hta_berichte/hta278_bericht_de.pdf (accessed on i December 2016).

- Franke, A.; Franzkowiak, P. Stress und Stressbewältigung. In Leitbegriffe der Gesundheitsförderung: Glossar; Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung, Ed.; Verlag für Gesundheitsförderung: Köln, Frg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- GKV-Spitzenverband (Ed.) Leitfaden Prävention 2014; Handlungsfelder und Kriterien des GKV-Spitzenverbandes zur Umsetzung der §§ twenty und 20a SGB V vom 21. Juni 2000 in der Fassung vom ten, Dezember 2014; GKV-Spitzenverband: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Russ, T.C.; Stamatakis, E.; Hamer, M.; Starr, J.Thousand.; Kivimaki, Thou.; Derailed, G.D. Clan between psychological distress and mortality: Individual participant pooled analysis of x prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2012, 345, e4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Greenish Version]

- Techniker-Krankenkasse. Entspann Dich, Federal republic of germany—TK-Stressstudie 2016. Bachelor online: https://world wide web.tk.de/ centaurus /servlet /contentblob/921466/Datei/177594/TK-Stressstudie%202016%20Pdf%20 barrierefrei.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2016).

- Currie, C.; Roberts, C.; Morgan, A.; Smith, R.; Settertobulte, W.; Samdal, O.; Rasmussen, V.B. Immature People's Health in Context. Wellness Behaviour in Schoolaged Children (HBSC) Study: International Written report from the 2001/2002 Survey; Word Wellness System: Copenhagen, Kingdom of denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Selye, H. The Stress of Life; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, U.s.a., 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.Due south.; Gruen, R.J.; DeLongis, A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, fifty, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, Due south. Stress: Appraisement and coping. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Springer: New York, NY, Us, 2013; pp. 1913–1915. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits, P.A. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Coping: Pitfalls and hope. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 745–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisement and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann, M.; Gmelch, S. Stressbewältigung. In Lehrbuch der Verhaltenstherapie; Margraf, J., Schneider, Due south., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, P.; Crane-Godreau, M.A. The preparatory set up: A novel approach to understanding stress, trauma, and the bodymind therapies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, Due south.C.; Fuchs, T. Embodied Arts Therapies. Arts Psychother. 2011, 38, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, J. Emotion, Psychosemantics, and Embodied Appraisals. R. Inst. Philos. Suppl. 2003, 52, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Salutogenese. Zur Entmystifizierung der Gesundheit. Forum für Verhaltenstherapie und Psychosoziale Praxis; Franke, A., Ed.; Dgvt: Tübingen, Germany, 1997; Book 36. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Southward.; Martin, 50. Verkörperte Ästhetik: Ein identitätsstiftender Wirkfaktor der Künstlerischen Therapien. In Spezifisches und Unspezifisches in den Künstlerischen Therapien; Tüpker, R., Gruber, H., Eds.; HPB University Press: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Book 6, pp. 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Due south.C. Arts and Health. Active factors and a theory framework of embodied aesthetics. Arts Psychother. 2017, 54, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oepen, R.; Gruber, H. Ein kunsttherapeutischer Projekttag zur Gesundheitsförderung bei Klienten aus Burnout-Selbsthilfegruppen—Eine explorative Studie. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2014, 64, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bräuninger, I. Trip the light fantastic toe move therapy group intervention in stress handling: A randomized controlled trial (RCT). Arts Psychother. 2012, 39, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkou, 5.; Sanderson, P. Arts Therapies: A Enquiry-Based Map of the Field; Elsevier Wellness Sciences: Oxford, Great britain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ECArTE—European Consortium for Arts Therapies Edcuation. Bachelor online: http://www.ecarte.info/ (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- Malchiodi, C.A. Expressive Therapies; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, Usa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Niff, S. Art-Based Research. In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples and Issues; Knowles, J.Thou., Cole, A.L., Eds.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, Usa, 2008; pp. 29–twoscore. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Musiktherapeutische Gesellschaft. Kasseler Thesen zur Musiktherapie. 2010. Available online: http://www.musiktherapie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/medien/pdf/Kasseler_Thesen_zur_Musiktherapie.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2017).

- Kunzmann, B.; Aldridge, D.; Gruber, H.; Wichelhaus, B. Künstlerische Therapien: Zusammenstellungen von Studien zu Künstlerischen Therapien in der Onkologie und Geriatrie: Hintergrund-Umsetzung-Perspektiven-Aufforderung. Musik Tanz Kunsttherapie 2015, 16, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, T.; Sappok, T.; Diefenbacher, A.; Dames, S.; Heinrich, M.; Ziegler, M.; Dziobek, I. Music-based Autism Diagnostics (MUSAD)—A newly adult diagnostic measure for adults with intellectual developmental disabilities suspected of autism. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 43, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Spreti, F. Kunsttherapie bei Psychischen Störungen, 1st ed.; Elsevier Urban & Fischer: München, Federal republic of germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, S.; Buxton, S.; Sheffield, D. The result of creative psychological interventions on psychological outcomes for adult cancer patients: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EADMT. Available online: http://www.eadmt.com/ (accessed on 1 November 2017).

- Hanna, J.L. Dancing for Wellness: Conquering and Preventing Stress; Rowman Altamira: Lanham, Dr., USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.; Koch, S.C.; Hirjak, D.; Fuchs, T. Overcoming Disembodiment: The Effect of Movement Therapy on Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia—A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Forepart. Psychol. 2016, vii, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, Due south.C.; Mergheim, K.; Raeke, J.; Riegner, Due east.; Machado, C.B.; Nolden, J.; Diermayr, G.; Moreau, D.; Hillecke, T. The Embodied Self in Parkinson'southward Illness: Feasibility of a Unmarried Tango Intervention for Assessing Changes in Psychological Health Outcomes and Aesthetic Experience. Front end. Neurosci. 2016, ten, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klees, S. A Hero's Journey in a German psychiatric hospital: A case study on the use of role method in individual drama therapy. Drama Ther. Rev. 2016, 2, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, R. Role theory and the role method of drama therapy. Curr. Approaches Drama Ther. 2009, 2, 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Acolin, J. The Listen–Body Connexion in Trip the light fantastic/Move Therapy: Theory and Empirical Support. Am. J. Trip the light fantastic Ther. 2016, 38, 311–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, H.; Rose, J.P.; Mannheim, E.; Weis, J. Künstlerische Therapien in der Onkologie—Wissenschaftlicher Kenntnisstand und Ergebnisse einer Studie. Musikther. Umsch. 2011, 32, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nawas, B.; Baulig, C.; Krummenauer, F. Von der Übersichtsarbeit zur Meta-Analyse—Möglichkeiten und Risiken. From Review to Meta Assay—Challenges and chances. Z. Zahnärztl. Impl. 2010, 26, 400–404. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Grading the Strength of a Body of Evidence When Assessing Health Intendance Interventions for the Effective Health Care Programme of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An Update. In Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews; AHRQ Publication: Rockville, Dr., U.s., 2013; Volume 13, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie; Mey, G., Mruck, Thou., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 601–613. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, K.; Shanahan, M.J.; Neufeld, R.W.J. Artistic tasks outperform nonartistic tasks for stress reduction. Art Ther. 2013, 30, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, Chiliad. Assessing Stress Reduction as a Function of Artistic Creation and Cognitive Focus. Art Ther. 2008, 25, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, Eastward.; Sarid, O. Visually transforming artwork and guided imagery every bit a way to reduce work related stress: A quantitative pilot study. Arts Psychother. 2014, 41, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, Yard.; Ray, K.; Muniz, J. Reduction of Cortisol Levels and Participants' Responses Post-obit Art Making. Art Ther. 2016, 33, 74–fourscore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimport, E.R.; Robbins, South.J. Efficacy of Artistic Clay Work for Reducing Negative Mood: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Art Ther. 2012, 29, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, A.; Warson, E.; Zhao, J. Visual journaling: An intervention to influence stress, anxiety and affect levels in medical students. Arts Psychother. 2010, 37, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, J. The Efficacy of Art and Writing Therapy: Increasing Positive Mental Health Outcomes and Participant Retention subsequently Exposure to Traumatic Experience. Fine art Ther. 2004, 21, v–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmire, D.A.; Gorham, Southward.R.; Rankin, Northward.E.; Grimm, D.R. The Influence of Art Making on Anxiety: A Pilot Report. Art Ther. 2012, 29, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrade, C.; Tronsky, L.; Kaiser, D.H. Physiological effects of mandala making in adults with intellectual inability. Arts Psychother. 2011, 38, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarski, K.; Leone, K.; Robbins, S.J. Reducing Negative Mood through Cartoon: Comparing Venting, Positive Expression, and Tracing. Art Ther. 2015, 32, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, South.M.; Martin, South.C.; Schmidt, L.A. Testing the Efficacy of a Creative-Arts Intervention with Family unit Caregivers of Patients with Cancer. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2004, 36, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, B.D.; Hansen, A.1000.; Gold, C. Coping with Work-Related Stress through Guided Imagery and Music (GIM): Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Music Ther. 2015, 52, 323–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodsky, West.; Sloboda, J.A. Clinical trial of a music generated vibrotactile therapeutic surroundings for musicians: Main furnishings and upshot differences between therapy subgroups. J. Music Ther. 1997, 34, 2–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.M.; Bradt, J.; Eyre, L.; Hunt, A.; Dileo, C. Creative approaches for reducing burnout in medical personnel. Arts Psychother. 2010, 37, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, Due south.R. The effect of sound, video, and paired audio-video stimuli on the experience of stress. J. Music Ther. 1996, 33, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Huang, Chiliad.-F. Effects of music therapy on psychological health of women during pregnancy. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 2580–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuRousseau, D.R.; Mindlin, M.; Insler, J.; Levin, I.I. Operational Study to Evaluate music-based neurotraining at improving sleep quality, mood and daytime function in a first responder population. J. Neurother. 2011, 15, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, L.C.; Pratt, R.R.; Madrigal, J.50. Music listening and A-lgA levels in patients undergoing a dental procedure. Int. J. Arts Med. 1998, v, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hatta, T.; Nakamura, M. Can antistress music tapes reduce mental stress? Stress Med. 1991, 7, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, G.; Rehana, R. Effects of Individual Music Playing and music listening on astute-stress recovery. Can. J. Music Ther. 2013, 19, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, S.50.; McKinney, C.H.; Holck, U. Effects of a dyadic music therapy intervention on parent-child interaction, parent stress, and parent-child relationship in families with emotionally neglected children: A randomized controlled trial. J. Music Ther. 2014, 51, 310–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-A. Predictors of Acculturative Stress among International Music Therapy Students in the United states. Music Ther. Perspect. 2011, 29, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiuk, T. The event of preferred music listening on stress levels of air traffic controllers. Arts Psychother. 2008, 35, one–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschi, T.; Bradley, C. Recreational Drumming: A creative arts intervention strategy for social piece of work teaching and practice. J. Baccalaureate Soc. Work 2010, 15, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, A.Z.; Shahabi, T.; Panah, F.M. An evaluation of the effect of group music therapy on stress, anxiety, and depression levels in nursing dwelling residents. Can. J. Music Ther. 2011, 17, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, E.M.; Nichols, J.; Somkuti, Southward.G.; Sobel, Chiliad.; Braverman, A.; Barmat, L.I. Randomized Trial of Harp Therapy During In Vitro Fertilization–Embryo Transfer. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 19, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rider, M.S.; Floyd, J.W.; Kirkpatrick, J. The Effect of Music, Imagery, and Relaxation on Adrenal Corticosteroids and the Re-entrainment of Cyclic Rhythms. J. Music Ther. 1985, 22, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Jagdev, T. Use of Music therapy for enhancing self-esteem amongst Academically Stressed Adolescents. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2012, 27, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.C.; Joyce, C.A. Mozart versus New Age Music: Relaxation States, Stress, and ABC Relaxation Theory. J. Music Ther. 2004, 41, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M. The Furnishings of a Unmarried Music Relaxation Session on Land Anxiety Levels of Adulats in a Workplace Surroundings. Aust. J. Music Ther. 2008, 19, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima, G.; Fukui, H.; Kuda, K. Piano playing reduces stress more than other creative art activities. Int. J. Music Educ. 2011, 29, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinniger, R.; Brownish, R.F.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; McKinley, P. Argentine tango dance compared to mindfulness meditation and a waiting-list control: A randomised trial for treating low. Complement. Ther. Med. 2012, 20, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinninger, R.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Brown, R.F.; McKinley, P. Intensive Tango Trip the light fantastic toe Plan for People with Cocky-Referred Affective Symptoms. Music Med. 2013, 5, fifteen–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga Murcia, C.; Bongard, Due south.; Kreutz, Grand. Emotional and neurohumoral responses to dancing tango argentino: The furnishings of music and partner. Music Med. 2009, 1, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Otte, C.; Geher, K.; Johnson, J.; Mohr, D.C. Furnishings of Hatha yoga and African trip the light fantastic toe on perceived stress, affect, and salivary cortisol. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 28, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedenhofer, S.; Koch, S.C. Active factors in trip the light fantastic toe/movement therapy: Specifying health effects of non-goal-orientation in motility. Arts Psychother. 2016, 52, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körlin, D.; Nybäck, H.; Goldberg, F.S. Creative arts groups in psychiatric intendance. Evolution and evaluation of a therapeutic alternative. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.C.; Kolter, A.; Kurz, T. Indikationen und Kontraindikation in der Tanz- und Bewegungstherapie. Eine induktive Bestandsaufnahme. Musik Tanz Kunsttherapie 2013, 23, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegemann, T.; Schmidt, H.-U. A pilot investigation on indication and contraindication of music therapy in child and adolescent psychiatry. Musikther. Umsch. 2010, 31, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Effigy 1. Menstruation-Nautical chart of the data base search on creative arts interventions for stress prevention.

Figure 1. Flow-Chart of the data base search on creative arts interventions for stress prevention.

Table 1. Overview of Efficacy Studies on Stress Prevention and Stress Management with Artistic Arts Interventions.

Tabular array 1. Overview of Efficacy Studies on Stress Prevention and Stress Management with Creative Arts Interventions.

| Study (Author/Year) | Level of Evidence | Object of Investigation | N/Sample | Pattern | Intervention | Methods | Exemplary Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Collection | Assay | |||||||

| ART THERAPY | ||||||||

| Abbott et al. (2013) [42] | Ib | Outcome of an creative action vs. art reception on the stress level | 52 Students, 34f/18m, M = 22.vii years | 2 × two factorial, randomized, controlled | Agile & passive creative condition: painting/drawing vs. viewing art; active/passive non-artistic condition: puzzle vs. viewing the puzzle pictures; one single interven-tion | Stress: Mental Arithmetic Task; Stress Induction Task, Stress Adjective Checklist; Creative Personality Calibration; Subjective Stress Scale | Multifactorial Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) | Stress reduction sig. higher in the grouping allocated to active artistic condition. F(two, 44) = 3.45, p < 0.05 |

| Scroll (2008) [43] | Ib | Short-term stress reduction by focusing on a positive, stress-free experience versus a negative, stressful feel during artistic activeness | 40 Psychology Students, 30f/10m, M = 19.65 years | 2 × 2 factorial, randomized, controlled | 4 experimental groups: drawing with positive and negative focus; creating collages with positive and negative focus; ane single intervention | Stress, anxiety: Land Trait Feet Inventory; drove of heartrate pre-mail Level of focusing on positive and negative experiences: Manipulation Check | t-test for independent samples; ANOVA | Focusing on positive experiences while creative activeness leads to stress reduction, regardless of the type of artistic technique. F(1) = 13.76, p < 0.01 |

| Huss & Sarid (2014) [44] | Ib | Effect of changing compositional elements (shape, size, color, texture) of a self-designed image of a memory vs. a uncomplicated retentiveness (guided imagery) on the experience of stress. | 35 Healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses, social workers) | Intervention-evaluation-study, randomized, controlled | Group I (Fine art Therapy): Amalgam a stressful piece of work experience on paper, transforming the feel into a stress-free event; Group II (Guided Imagery): introducing and recalling a stressful piece of work experience, 2 days workshop | Definition of creative elements: Compositional Elements Scale Discomfort, Stress: Subjective Units of Discomfort Scale (SUDS) | Descriptive: frequency analysis of compositional elements, paired significance tests, mean and standard difference calculation of private values | Reduction of stress level in Group I and Group 2. The compositional elements of shape, size and color are of particular importance. X 2 = eight.61(df = ane), p = 0.03; X ii = 7.56(df = 1), p = 0.04; t-test = 3.27(df = 1), p = 0.03, t-test = ii.03(df = ane), p = 0.04, respectively |

| Kaimal, Ray & Muniz (2016) [45] | IIb | The bear on of visual art making on the cortisol level | 39 Students, staff & faculty from a large university, 33f/6m, K = 38.88 | Single arm, pre-postal service-design, quasi-experimental | 1 single session: 45 min of art making using collage materials, modeling dirt, and/or markers, fifteen min for consent and data collection earlier and after the session | Cortisol Level: Saliva Sample (pre/post; ELISA kit method) Prior Art making feel: limited, some, extensive feel cocky-reported perceived bear on of art making: Written responses from participants (qualitative data) converted into numeric data, entered into quantitative database | t-examination for paired samples, one-way ANOVA, t-test for contained samples, Correlation Analysis: | Sig. reductions in cortisol following the intervention: cortisol levels pre- and posttest differed significantly t(38) = 4.54, p < 0.01 No sig. differences based on prior experiences on cortisol levels, F(2, 36) = 0.64, p = 0.53 No sig. differences based on gender on changes in cortisol, t(37) = 0.456, p = 0.65 Cocky-reported themes were non strongly correlated with changes in cortisol levels |

| Kimport & Robbins (2012) [46] | Ib | Outcome of a guided intervention with dirt on the mood | 102 Students of an American University, 74f/28m, 1000 = 22.3 years | ii × ii × 3 factorial, randomized, controlled | Creation of negative mood by showing a brusque film; 4 different v-min interventions: Group A: dirt + instruction; Group B: clay without teaching; Group C: stress ball + Educational activity; Group D: stress ball without instruction; 1 single session | Mood State, Anxiety: Contour of Mood States (POMS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | Multifactorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | Editing tone (with and without instruction) reduces negative mood (mood and anxiety) more than working with stress assurance; guided interventions (clay and balls) reduce negative mood more than interventions without guidance; POMS: F(1, 98) = vii.vi, p < 0.05; STAI-S: F(1, 98) = iv.4, p < 0.05. |

| Mercer et al. (2010) [47] | 3 | Stress reduction through visualization (Visual Journaling) | 10 5 medical Students, 5 Lecturers | Single-arm, pre-post-design with follow-upwardly | Visualization of a stress-inducing vs. a stress-complimentary emotion, drawing of these emotions, self-explanatory questions for a improve agreement of the stress situation; i single intervention | Mood State, Anxiety: quantitative: State-Trait Feet Inventory (STAI-Y), the Positive and Negative Impact Schedule (PANAS) qualitative: Questions on stress situation | paired t-tests | Non-significant reduction of anxiety and improvement of mood. |

| Pizarro (2004) [48] | Ib | Comparing of art and writing therapy concerning their effects on psychological and health conditions | 45 Students, 27f/18m, K = 19 years | randomized, controlled, pre-post-design with follow-up | 2 experimental groups: Induction of a stressful situation based on a text; painting this situation (art-stress) vs. writing most this state of affairs (write-stress); control group: painting a still life later a neutral text, 2 sessions on ii days | Health, Stress, Physical Symptoms, Mood: Full general Health Questionaire (GHQ-28), The Global Measure of Perceived Stress (GMPS), Physical Symptoms Inventory (PSI), Contour of Mood States (POMS) (short version) qualitative: Questioning on satisfaction; Questionnaire for the Assessment of stress reduction in art and writing intervention (follow-upward) | Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) | Sig. reduction of social dysfunction in the writing-stress group: F(ii, 37) = iii.17, p = 0.05; No health improvements in the art groups: F(2, 37) = 0.x, ns; Merely more joy and commitment of study participation in the fine art groups. |

| Sandmire et al. (2012) [49] | Ib | Reduction of anxiety through artistic activity | 57 Students, 45f/12m, M = 18.viii years | randomized, controlled | experimental grouping: Choice of one of v artistic activities (mandala, gratuitous painting, collage, clay, drawing), one single session, duration: 30 min.; command group: no intervention | Anxiety: Land Trait Feet Inventory (STAI) | t-tests for paired samples; multifactorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | Sig. reduction of feet (state and trait) before concluding exams. p < 0.001, F(1) = 12.72 |

| Schrade et al. (2011) [50] | Ib | Relaxation and reduction of stress levels through painting mandalas. | 15 Adults with mental disabilities 9f/10m | Repeated measure, randomized, controlled | 3 weather: painting mandalas, free painting, neutral command status (puzzle, lath games, etc.), 1 single session | Stress: claret force per unit area, pulse (Sphygmomanometers) | three split up ANOVAs for repeated measures | Sig. reduction of blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) in the mandala group over fourth dimension: F(2, 28) = half dozen.05, p < 0.05; no sig. change of stress levels comparing the iii groups. |

| Smolarski et al. (2015) [51] | Ib | Upshot of instructions on emotional expression on the mood-enhancing qualities of drawing | 45 Students, 28f/17m | randomized, controlled, doubleblind, pre-post design | 1. Inducing a negative mood 2. Randomized allotment to 3 groups: Group A: drawing happiness (acting out a positive mood) Group B: drawing current stress (acting out a negative mood) Group C: tracing and coloring a simple drawing (control group, lark strategy), 1 single session | Mood State: Profile of Mood States (POMS) | two-factorial ANOVA with repeated measures (iii groups; time: baseline, pre-postal service-treatment) | Sig. mood comeback through the expression of a positive emotion while drawing in comparison to the expression of a negative emotion (venting) or the drawing of uncomplicated lines (control group), F(ii, 42) = 4.0, p < 0.05. |

| Walsh et al. (2004) [52] | IIb | Outcome of an artistic intervention on feet and stress among family members of cancer patients | 40 family unit members of cancer patients, 30f/10m, Chiliad = 51.43 years | pre-postal service-blueprint, quasi-experimental | Creative-creative intervention, e.grand., painting mandalas, painting; Implementation in the infirmary room of the patient, ane unmarried intervention | Mood Land: Mini-POMS Feet: Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) Negative and positive emotions: Derogatis Affects Balance Scale (DABS) | t-tests for paired samples | Sig. reduction of stress, anxiety: t(xl) = −three.42, p = 0.001; increase of positive emotions, t(46) = 11.87, p < 0.001. |

| MUSIC THERAPY | ||||||||

| Beck, Hansen & Gold (2015) [53] | Ib | Effect of MT on biopsychosocial parameter | 20 Danish workers with stress-related incapacity to piece of work, 16f/4m, Chiliad = 45.5 years | randomized, controlled | Music Therapeutic Intervention: Guided Imagery and Music (GIM) ii-hour-sessions, 6 sessions in 9 weeks | Cortisol, testosterone, melatonin: analysis of saliva in the laboratory Stress: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS); Profile of Moods States (POMS-37); Visual counterpart scale for immediate stress sensation before and subsequently the sessions; Karolinska Sleep Diary (KSQ); Unpublished 16-item scale for physical stress symptoms Willingness to work: single item Well-being: WHO-5 Well-Beingness Index Feet: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) Low: Major Low Inventory | t-test for independent samples | Sig. comeback in well-beingness and sig. reduction in sleep disturbance and physical distress. Early intervention leads to faster re-entry of work & positive sig. effects on stress, mood, slumber disorder, depression, feet and concrete symptoms of distress. (run across Table 2, p. 339, in original study) |

| Brodsky & Sloboda (1997) [54] | Ib | Comparison of result of Music Therapy and traditional verbal Psychotherapy | 55 Musician of a symphony orchestra, M = 36 years | randomized, controlled, pre/post design with follow-up | Iii groups: (a) Somatron: traditional verbal psychotherapy, abbreviated progressive relaxation preparation (APRT), recorded music complemented by music-generated vibrations (b) Music: verbal psychotherapeutic counseling, APRT relaxation exercises supplemented with recorded music (c) Counseling: exact psychotherapeutic counseling 1 h per calendar week, 8 weeks | Baseline (Anxiety, Stress, Mood Land, Burnout): General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Derogatis Stress Profile (DSP), Profile of Mood States (POMS), Maslach Exhaustion Inventory of Music Performer's Stress (AMPS), and the Music Performance Stress Survey (MPSS) Pre-Post (Mood State, Relaxation): POMS, relaxation exercises | Multifactorial ANOVA with repeated measures | Music-supported forms of therapy equally efficient as traditional counseling. 14 of the 52 sets of variables were statistically and clinically significant at measuring fourth dimension 2 and 3. Differences between groups were not sig. F(ii.46) = 4.16; p = 0.22. |

| Brooks, Bradt, Eyre, Chase & Dileo (2010) [55] | Ib | Effect of MT on cocky-assessment of burnout, sense of coherence and job satisfaction | 65 Medical nursing staff, 43f/9m M = 42.16 years | Randomized, controlled | Guided Imagery with music and relaxation exercises, 3-vi weeks, 60 min sessions | Exhaustion: Maslach Burnout Inventory Sense of Coherence: Sense of Coherence Scale Job Satisfaction: Task Satisfaction Survey Individual perception of interventions: Self-report on interventions (qualitative survey) | Independent t-test Grounded theory | Quantitative results: No sig. differences between experimental group (MT) and control grouping (waiting). Qualitative results: Music therapeutic Intervention helped subjects to relax and to recharge energy. |

| Byrnes (1996) [56] | Ib | Consequence of audio, video and audio-video stimuli on the stress experience | 54 33 Adults (participants of a university summer grade) 21 students of music and/or education | Randomized, controlled, pre-postal service-design | Three groups: (a) Audio-Video: Music-Video excerpt from "Tropical Sweets" (with classical music) (b) Audio: "Aquarium" by Camille Saint-Saens (c) Video: Underwater pic about tropical marine life, 1 single session | Questionnaire on socio-demographic data, music preferences and activities for relaxation, current level of stress Stress Feel Continuous Response Digital Interface (CRDI) | Paired t-tests | Stress reduction especially for participants with a high level of stress at the showtime: t = three.695, df = 53, p = 0.001; Sig. reduction in audio-video condition, sound or video status alone did not sig. touch stress. |

| Chang, Chen & Huang (2008) [57] | Ib | Effect of MT on the stress level, anxiety and the degree of depression | 236 pregnant, Taiwanese women One thousand = 30.48 years | randomized, controlled | EG: passive music therapy intervention: listening to music 2 weeks, 30 min. per day CG: general prenatal handling without MT | Stress: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Anxiety: Land Scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (S-STAI) Depression: Edinburgh Postnatal Low Scale (EPDS) | Paired t-examination Assay of Covariance (ANCOVA) | Stress reduction, anxiety reduction and reduction of the caste of depression sig. higher in the EG with music therapy intervention than in the CG (run across Table iv, p. 2585, in the original written report). |

| Du Rousseau et al. (2011) [58] | IIa | Improvement of sleep quality, mood state, everyday functions | 41 Police enforcement officers, firefighters, 13f/28m | pre-postal service-design, controlled | Brain Music (BM) Music-based Neurofeedback Therapy | Insomnia, sleep quality, depression, life satisfaction, everyday functions: Pittsburgh Insomnia Rating Scale, Subjective Sleep Questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory, Life Satisfaction Scale, Daytime Functioning Scale, 4 weeks intervention | Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), paired t-tests | Sig. comeback of sleeping quality, insomnia, mood and everyday performance (see Table 1, p. 392, in the original study). |

| Goff et al. (1998) [59] | Ib | Comparison of the effects of music and nitrous oxide on the pain-, anxiety- and stress-levels of subjects during a dental treatment | 80 dental patients | randomized, controlled, two × ii factorial | (a) treatment under nitrous oxide and Level ane = no music/level 2 = with music (b) handling accompanied past self-selected music (Level i = without nitrous oxide, level 2 = with nitrous oxide) | Pain, Anxiety, Stress: Saliva samples before and afterward treatment for decision of S-IgA concentration (secretory immunoglobulins A) | multifactorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | No sig. differences between the two handling methods; in women sig. stress reduction with music accompaniment (run into Tables one and 2, p. 24, in the original written report). |

| Hatta & Nakamura (1991) [60] | Ib | Effect of Anti-stress Music-CDs on stress level | 52 Students, 28f/24m | Randomized, controlled, Pre-Mail service-Design | EG: Classical Music vs. Nature Sounds vs. Pop music; CG: no intervention, single session | Stress, Arousal: Stress/Arousal adjective checklist (SACL) | 2-factorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | Sig. reduction of stress and arousal through listening to music, regardless of the type of music, F(9, 144) = 4.25, p < 0.01. |

| Ilie & Rehana (2013) [61] | Ib | Effect of playing music on the iPhone on the acute stress level | 54 Students, 27f/27m | Randomized, controlled, 2 × iii factorial, pre-post-design | Group ane: induction of a stress state of affairs Grouping ii: no stress induction Each: (a) Pressing the music app "Smule Ocarina" for 10 min, i.east., Playing the tune "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" (b) listening to the melody; (c) Sitting quietly 1 unmarried session | Mood Land, Arousal: Profile of Mood States (POMS) Level of Cortisol: Salimetrics Oral Swab (SOS) | Mixed-model ANOVA | Sig. reduction of cortisol level in the stress-induced group past listening to or playing the app compared to the control group, F(i, 65) = 21.54, p < 0.001. |

| Jacobsen, McKinney & Holck (2014) [62] | Ib | Effect of MT on the parent-child interaction and parent-child human relationship equally well as the stress experience of the parents | eighteen Parent-child dyads from Denmark with neglected children | Randomized, controlled | EG: music therapeutic Intervention CG: standard handling without MT 10 weekly sessions, 45 to 50 min. | Parent Competencies: Cess of Parenting Competencies (APC) Stress feel of parents: Parenting Stress Alphabetize (PSI) Parent-Child-Human relationship: Parent-Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI) | Multifactorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | Improvement of parent competencies and parent-child interaction, too as stress reduction in the experimental group with MT intervention higher than in the command group (see pp. 321–326 in original study). |

| Kim (2008) [63] | Ib | Effect of two music therapy approaches on Music Performance Feet (MPA) | xxx Music Students (Piano) | Randomized, controlled, pre-mail-design | 2 Groups (a) improved-music-assisted-desensitization-group (b) music-assisted progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) and imagery-group half-dozen weekly sessions | Anxiety, Stress, tension, relaxation: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Music Performance Anxiety Questionnaire (MPAQ); Measurement of the finger temperature | Tests of significance, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | Sig. reduction of MPA in the music-assisted desensitization group at 6 out of 7 measurement points; Anxiety reduction in the music-assisted PMR group to a lesser extent than in the former group, only sig. for stress and tension level. Level of tension: F = 7.55, p = 0.016, df = 1, 14; country anxiety of the STAI, F = v.57, p = 0.033, df = I, xiv; finger temperature measure out, F = 7.87, p = 0.014, df = i, 14 |

| Lesiuk (2008) [64] | Ib | Consequence of listening to self-selected music at the workplace on stress levels | 33 air traffic controllers, 2f/31m, M = 34 years | Randomized, controlled; Pre-Post-Design | EG: 15 min. Listening to favorite music, in the interruption of four working shifts in 2 weeks; CG: sitting in silence instead of listening to music | Extraversion, Introversion: Eysenck Personality Inventory; Anxiety: State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory (STAI); Measurement of heart charge per unit, claret pressure, state anxiety and subjectively perceived aviation activity | Multifactorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | No sig. differences between physiological and psychological components in the comparison of both groups; Sig. anxiety reduction (state anxiety) in EG and CG over time, F = 19.22, d.f. = 2, p = 0.000, and reduced perception of air traffic in both groups. |

| Maschi & Bradley (2010) [65] | III | Outcome of relaxation drums on well-being, empowerment and social connectedness | 31 Social Work Students, 29f/2m | Pre-Post-Design | One single session of two h relaxation drumming in the grouping | Stress, Energy, Empowerment, Bonding: Session Impact Scale | paired t-tests | Sig. stress reduction, increased energy, empowerment and a sense of community (see Table three, p. 61, in the original report). |

| Mohammadi, Shahabi & Panah (2011) [66] | Ib | Result of MT on stress, feet and the degree of low | xix residents of a home for elderly, 9f/10m, Chiliad = 69.4 years | Randomized, controlled | Experimental Group: MT group intervention (music listening, singing, percussion), 10 weeks of ninety min. daily sessions Control group: standard day-to-solar day acitivities | Stress, Feet & Low: Depression Anxiety Stress Calibration (DASS) | Isle of man-Whitney U-Test | Stress reduction, anxiety reduction and reduction of the degree of depression sig. higher in the experimental group with MT than in the command group (standard mean solar day-to-twenty-four hour period activities) (see Table 1, p. 63, in the original study). |

| Murphy et al. (2014) [67] | Ib | Outcome of harp therapy on the stress level and clinical outcome values | 181 Women in an in vitro reproduction surgery | Prospective, randomized, controlled, pre-mail design | EG: harp therapy for in vitro fertilization CG: standard therapy | Anxiety: Land-Trait Feet Inventory; Pulse, respiratory charge per unit, blood pressure | t-test for paired samples, Wilcoxon rang sum test | Sig. college reduction of anxiety (land anxiety) over time in the EG than in the CG; Formulation charge per unit higher in EG than in CG; positive effect on the astute stress level; no sig. Improvement of eye rate and respiratory rate (see Tables vi–nine, pp. 96–97, in the original written report). |

| Passenger et al. (1985) [68] | III | Effect of music/progressive musculus relaxation (PMR)/guided imagery (GI) on stress hormones | 12 Nurses | Quasi-experimental, pre-post design | 20-min program of classical music (audio cassettes) incl. PMR and GI (visualization of imaginative images); 5 times a calendar week over three months | Adrenal Corticosteroid (Stress hormones): Urine samples, temperature measurements; Taylor-Johnson Temperament Assay, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Torrance Test of Creativity, Circadian Type Questionnaire | t-tests | Reduction of circadian amplitude and corticosteroid temperature rhythms during music listening; The boilerplate corticosteroid level did not improve sig. over fourth dimension. |

| Sharma & Jagdev (2012) [69] | Ib | Outcome of MT on the self-esteem of adolescents | sixty adolescents with loftier school stress levels & depression self-esteem, M = 16.85 years | pre-post blueprint, controlled | EG: 30 min listening to classical Indian music (raga, flute) per mean solar day, 15 days; CG: discussion of study irrelevant topics | School Stress (Feet, Frustration, Pressure Conflict): Scale of Academic Stress (SAS-3) Self Esteem: Self Esteem Inventory (SEI) | t-tests | Sig. increase in cocky-esteem in the EG compared to the CG. (see Table ii, p. 59, in the original report) |

| Smith & Joyce (2004) [70] | IIa | Effect of MT on the state of relaxation and stress | 63 students, 45f/18m, M = 20.88 years | Quasi-experimental, controlled | EG1: receptive MT-Intervention (Mozart). EG2: receptive MT-Intervention (New Historic period Music) CG: reading offer without MT Relaxation Sessions of 28 min, 3 days in a row, once a solar day | State of Relaxation and Stress: Smith Relaxation States Inventory (SRSI) | Pearson chi2-exam | Stress reduction and increment of the relaxation land higher in EG1 (Mozart) compared to EG2 (New Age Music) or to the control grouping (reading of leisure magazines). (see p. 220) |

| Smith (2008) [71] | Ib | Effect of MT on Anxiety | 80 Employees of a call center 40f/40m, G = 37.5 years | Randomized, controlled | Experimental group: Progressive musculus relaxation with music Control group: verbal discussion, i single session | Anxiety: State Trait Anxiety Inventory | t-test with repeated measures | Anxiety reduction sig. higher in the EG with musical relaxation intervention than in the CG (verbal discussion): decrease in tense rating: t(39) = 12; p < 0.01; increase in pleasant and relaxed rating: t(39) = −xx.27; p < 0.01; t(39) = −sixteen.2; p < 0.01. |

| Toyoshima, Fukui & Kuda (2011) [72] | Ib | Effect of creative activities on cortisol levels and feet | 57 Students, 30f/27m, M = 21.5 years | Randomized, controlled | Three experimental groups (1 piano playing, ii clay modulations, 3 calligraphy) and a control group (lingering in silence) ane single session | Anxiety: State Trait Feet Inventory Detection of cortisol in saliva | Multifactorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | Anxiety reduction and cortisol deposition higher in the EG (creative interventions) than in the CG (lingering in silence). Playing the piano shows the biggest effects. F(1,113) = five.57, p = 0.0202 |

| DANCE/Movement THERAPY | ||||||||

| Bräuninger (2012) [21] | Ib | Comeback of stress management and stress reduction, likewise equally the influence of DMT group intervention on quality of life (QoL) | North = 162 Clients suffering from stress (self-assessed), 147f/15m G = 44 years | Randomized, controlled, pre-post-design with follow-up after 6 months | EG: DMT, grouping intervention, ten weeks CG: waiting control grouping | Stress management and stress reduction: Stress processing questionnaire/SVF 120 Full general Stress Level and Psychopathology (Brief Symptom Inventory/BSI) Quality of Life (QoL): The World Health System Quality of Life Questionnaire 100 (WHOQOL-100) and Munich Life Dimension List (MLDL) | Stress Data: Multifactorial Assay of Variance (ANOVA) Quality of Life: Analysis of Variance with repeated measures (repeated measures ANOVA) | Negative stress management strategies decreased sig. in short and long term comparisons, positive strategies of distraction increased, as well every bit relaxation; sig. short-term improvements in the BSI, especially with regard to feet scores; QoL dimensions were sig. better in the EG than in the CG (meet Tables 4 and 5, pp. 447–448, in the original study). |

| Pinninger, Brownish & McKinley (2012) [73] | Ib | Comparison of tango and mindfulness meditation regarding stress reduction, reduction of anxiety and depression symptoms and improvement of well-beingness | Sample N = 79 (cocky-assessed) depressedPersons, 19.5f/80.5, M = 38.68 years | three × 2 factorial blueprint, randomized-controlled, pre-post exam | 3 interventions: Tango: vi weeks, i ½ h per week Mindfulness meditation: half-dozen weeks, i ½ h per week Waiting control group | Feet, Depression: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Calibration (DASS-21-Scale); Rosenberg Self Esteem Calibration; Satisfaction with Life Calibration, and Mindful Attention Sensation Scale. | Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) and Multiple regression analysis | Significantly reduced depression symptoms in both (F(2, 59) = 6.00, p = 0.004), the tango group and the mindfulness group compared to the control group; reduced stress only in the tango grouping (F(ii, 59) = iii.88, p = 0.026); participation in the tango dance was a pregnant predictor of improved mindfulness. |

| Pinninger, Chocolate-brown & McKinley (2013) [74] | Ib | Effect of an intensive program of Tango dance on cocky-reported stress, anxiety or symptoms of low | N = 41 (experimental grouping: xx, waiting control grouping: 21) | Randomized, controlled (RCT) Pre, Mail-Test, follow-upwards afterward one month | EG: Tango dance program (4 × i ½ h in 2 weeks), waiting control group | Self-assessment scales of stress, anxiety and depression symptoms: Low Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21); Indisposition Severity Index; Satisfaction with Life Calibration; Full general Cocky-efficacy Scale; Mindful Attending Awareness Scale; Qualitative feedback | Analyzes of Covariance (ANCOVAs) | Self-assessed stress-, anxiety- and low-symptoms in the experimental group sig. improved compared to the command grouping; effects were retained at follow-up time (1 month); life satisfaction and cocky-efficacy sig. improved; mindfulness did not change sig.: stress, F(i,38) = 12.59, p = 0.001; feet, F(i,38) = 8.31, p = 0.006; depression, F(one,38) = 25.60, p = 0.001; insomnia, F(one,38) = eight. xxx, p = 0.006 |

| Quiroga Murcia, Bongard & Kreutz (2009) [75] | IIa | Effects of tango dance on psychophysiological emotion or stress measurements | 22 healthy individuals with min. 1 year tango experience, 11f/11m M = 43.09 years | 2 × ii factorial, controlled | 4 Conditions: ane. Regular tango trip the light fantastic toe with partner and music 2. Tango dance with partner without music iii. Dance without partner merely with music iv. Motion without a partner and without music 20 min sessions | Stress: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) Saliva samples for the study of cortisol and testosterone | Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) with repeated measures | Sig. reduction of negative affect, sig. improvement of positive bear on (F(1, 21) = 5.06, p < 0.05), and sig. reduction of cortisol concentration in saliva through tango dance with music and partner (F(1, 19)= five.45, p < 0.05). The effect was dependent on the music, but not on the partner. |

| West et al. (2004) [76] | IIa | Comparing of African Dance and Hatha Yoga regarding their influence on well-being | 69 Students 47f/22m Grand = 19 years | iii × iii factorial, controlled | 3 Conditions: 1. Hatha Yoga ii. African Dance 3. Biology Lecture 90 min courses, single session | Stress: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), saliva samples for the measurement of cortisol | Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) with repeated measures | Sig. reduction of perceived stress and negative touch too as improvement of the positive impact in Hatha Yoga and in African dance: F(2, 66) =11.77, p < 0.0001; Sig. reduction in cortisol concentration in saliva in the yoga condition (F(2, 59) = 17.28, p < 0.0001); Increase of cortisol in saliva in the trip the light fantastic toe condition and no change of cortisol in the control status. |

| Wiedenhofer & Koch (2016) [77] | IIa | Comparison of non-goal-directed movement and goal-directed movement in terms of their influence on stress and well-existence | North = 57 Students, 44f/12m M = 23.21 | Two-factorial, controlled, pre-post pattern | EG: not-goal-directed motion improvisation to music, one-fourth dimension participation twoscore–l min. CG: goal-directed motion improvisation to the same music. Colorful mail service it-notes were used as target points in the room, one-fourth dimension participation | Perceived Stress: PSQ30 questionnaire Well-being: HSI (Heidelberg State Inventory) Self-efficacy: Full general Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE scale) Trunk-self-efficacy: Cocky-Efficacy-Calibration (BSE) | MANOVA with repeated measures t-tests for paired samples | Perceived stress in EG sig. more than reduced than in CG F(56,1) = 4.71, p = 0.034 ; Trunk-Self-efficacy increased sig. in EG F(56,1) = vii.00, p = 0.011, no difference in well-beingness:. |

Table ii. Overview of the reviewed studies. Evidence levels are defined according to AHRQ [40].

Table two. Overview of the reviewed studies. Prove levels are defined according to AHRQ [twoscore].

| Time of Publication | Show Level | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arts Modality | 1980–1999 | 2000–2016 | Full | Ib | IIa | IIb | 3 |

| Art therapy/art interventions | 0 (0/0) | 11 (0/eleven) | 11 (0/11) | 8 (0/8) | 0 (0/0) | 2 (0/2) | 1 (0/1) |

| Music therapy/music interventions | 5 (1/4) | fifteen (10/5) | 20 ( 11 /9) | 16 (9/7) | 2 (2/0) | 0 (0/0) | ii (0/2) |

| Trip the light fantastic/move therapy/dance interventions | 0 (0/0) | 6 (i/5) | 6 (ane/5) | 3 (one/2) | 3 (0/3) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) |

| Drama therapy/drama interventions | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) |

| Total | five | 32 | 37 | 27 | v | 2 | 3 |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC Past) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/8/2/28/htm

0 Response to "Pratt R Art Dance and Music Therapy Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2004"

Post a Comment